What can a village teach a city about design, leisure and spirituality?

At first, these topics seem unrelated to sustainability. That's because we often consider sustainability as separate from the whole system. Let me change that for you. (Reading time: 10 minutes)

Dear readers,

I had to take a break from writing your favourite newsletter because I was staying in a village in Madhya Pradesh for a few weeks.

As part of the Youth Alliance team, I was helping a group of 24 individuals who had come together from different parts of India, and from different backgrounds to explore themselves, other people in the cohort and the communities in a village.

In this post, I want to share some of my observations while staying there. You’ll have to slow down to read this one.

.

Since a year, I have been on a quest to answer the question - what is sustainable?

It’s clear that sustainability is not just about electric vehicles, renewable energy, climate solutions, climate finance, CO2 capture, global warming, biodiversity and conservation.

It’s a lot deeper and broader — it’s the entire system we are a part of. It includes how our cities, villages and spaces are designed, the concentration of wealth in a few hands, the idea of ‘development’, how the economy of a place works, what does it incentivize, how our production and consumption models are built, who or what they prioritize, how are we spending our free time and many more such questions.

Spending time in this village helped me understand a little bit more about what used to be, what we need to conserve and protect going forward and what we need more of in our cities.

1. Design

The first thing that always strikes me when I visit the village Indrana is the height of the walls of people’s homes. They are just so low.

As you walk through the village, you can easily see what’s happening in each house on your left and right. While you can’t see inside the rooms, you can see into the ‘aangan’ — the open space just outside the main structure of the house.

This space is simply mud, which allows rainwater to percolate back into the earth, unlike tiled surfaces that block groundwater recharge in our cities.

Then the open doors of most houses. The open door policy in offices might well have been inspired by villages like this, where most homes keep their main door open. It’s a small detail, but it makes the space feel incredibly welcoming.

It was fascinating for me to see that even a cow was welcome!

This curious cow was loitering around in a shop selling water coolers (see photo above). Unlike a bull in a china shop, it didn’t break or destroy anything. It was gently ushered out—not by the shopkeeper (who wasn’t there at the time)—but by a complete stranger standing 2–3 shops away.

This stood out to me in stark contrast to city life, where I’ve noticed walls of houses getting taller and taller—as if they’ve been raised on a diet of Bournvita and Horlicks. And our main gates are almost always closed—for security, or to keep stray animals and strangers out.

It feels like the more wealth we accumulate, the taller the walls of our houses become—so that no one can peek inside. As we grow "richer" or more materially secure, our need for privacy seems to grow too, accompanied by a subtle mistrust of others and a fear that our possessions may be taken away.

But let me get back to the village. Many houses in the village have a step-like structure right outside. It's a small raised platform where anyone passing by can pause, take a breath, relax, or simply sit and chat with someone inside.

It’s a subtle but beautiful space that encourages community interaction. It’s a small but thoughtful design aspect that again, welcomes you in, not keep you out as much as possible.

The streets, too, are designed for connection. They’re wide enough for people to walk, but not wide enough to allow cars to cause traffic jams. Bicycles are common, though increasingly, motorcycles—with loud, deafening horns—are seen.

We often admire European cities for being walkable and bicycle-friendly which they are. But we forget that India’s villages were always designed with walkability in mind.

Indrana is small, home to about 10,000 families, and it doesn’t seem to be expanding rapidly. Compare this with Indian cities, which constantly push outward—devouring surrounding land and beautiful green pastures.

It makes me wonder: Is it truly sustainable to keep expanding cities into nearby areas? Or would it be wiser to invest time, money, and effort into nurturing villages—so cities don’t have to bear the entire burden of growth?

2. Leisure time

One Wednesday afternoon, the six of us were strolling through the village when we stopped by a house I had never visited before.

There, I saw a 12-year-old boy crafting various vehicles out of used tea cartons and bottle caps. He’d tied them with a string and was pulling them along like toys. Before I could call my group over to admire his D-I-Y creations, the boy quickly hid them away, as his parents—perhaps half-joking—complained, “He doesn’t spend time studying… all his brain goes into making this kind of stuff.”

In the city, we often see “make from waste” workshops at sustainability events, inspiring people to do what this boy was doing intuitively in his free time. That’s what leisure can offer—an invitation to create when boredom sets in. His father runs a small jewelry business in the village and can afford to buy a new toy for him if he wishes. But the joy of creating your own is different.

However, that’s not why I’m telling you this story.

बात करते करते हमें पता चला कि ये बच्चा ढोलक भी बजाता है।

We got excited and asked him to bring it out. He returned not just with the dholak, but with several other instruments. And within minutes, the whole scene transformed.

His mother became the lead singer, singing bhajans of Ram and Krishna while we followed along. We were handed various instruments and tried our best to keep up, while the boy expertly played the dholak.

What stayed with me for days was the spontaneity of that moment—how, on a random weekday afternoon, we visited a stranger’s home, jammed with them, and walked away with a memory.

I’ve never experienced that in a city. And I wish such moments were even possible there.

In cities, the barriers to entering a stranger’s home are too many. And even if you do, they’re unlikely to hand over instruments and start singing freely. That kind of uninhibited sharing of joy feels increasingly rare.

And, will you ever find the entire family having enough leisure time on a weekday afternoon to just sit and jam with strangers? Strangely, with more machines and appliances at our disposal, we still don’t seem to have enough free time to live life.

3. Spirituality and religion

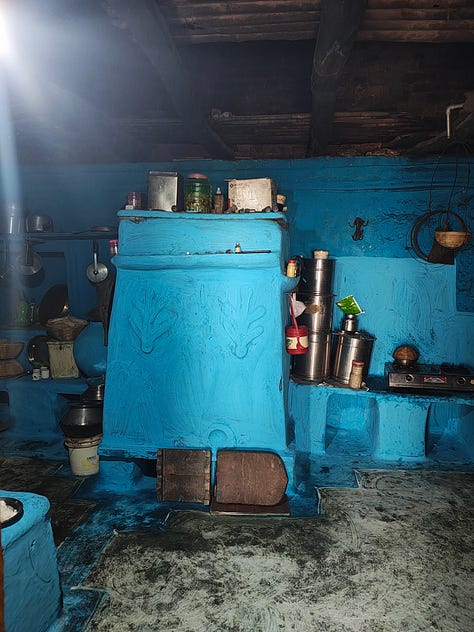

There is a village elder (Sundar kaka) who lives by the river—he has a room with a view (see picture below). He is a fisherman, goat-shepherd, and part-time farmer all rolled into one.

He studied in a gurukul for 12 years and can recite the Ramcharitmanas as effortlessly as a child sings "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star." He can’t read or write, but he knows exactly which page a particular shloka appears on.

In casual conversation, he drops profound insights like:

“ज्ञान एक बाल से भी सूक्ष्म होता है। देखने वाली की नज़र होनी चाहिए।” (Knowledge is finer than a strand of hair. Only a true seeker can perceive it.)

He’s not the only one. Another villager, in an equally casual tone, said to me during the visit: “भगवान तो सबको मिले हैं, हम बस पहचान नहीं पाए हैं।” (Everyone has received God… we just haven’t recognized Him.)

I really wasn’t expecting that.

Every morning from 7:30 to 9 AM, some children in the village—mostly 12 year old and younger—attend a Gita course in the village temple. The course includes an exam with questions about the Mahabharata. But as you turn the pages, you encounter deeper reflections—like: ‘ईश्वर क्या है?’

In cities, I rarely see parents investing their kids’ time in learning about texts like the Gita. It’s usually classes in dance, music, sports, or gym. Don’t get me wrong—physical activity is essential for a child’s development. But so is the nurturing of values.

And ultimately, it’s those values that guide whether a person’s actions, as an adult, will be in harmony with other people in the world—or in harmony with the market.

4. Circularity

It was great to see circularity in action in the village - a concept often talked about in sustainability circles. The waste materials of one community were being used as raw materials by another community.

The only waste we noticed in the village were plastic wrappers from packaged products—thanks to big FMCG companies targeting rural India to increase their sales.

For instance, a community in the village owns two horses that, among other things, are used for weddings. The dung of these horses is taken by a potter family and mixed with clay to make it porous for pottery. In return, the potter family (led by the village elder Dassu kaka) gives the horse owners either finished pots or grains from their farm.

Another thing common at Indian weddings are endless gifts and rituals, all of which require some kind of storage.

So another village elder named Halke kaka and his family make bamboo baskets in different sizes and weaving patterns, each designed for specific rituals during the wedding for various families in the village. Once their purpose is served, the bamboo decomposes and goes back into the earth.

Now imagine the amount of waste we generate in our city weddings—the plastic packaging, the gift wraps, and the general overuse of non-biodegradable materials for all the rituals so the pictures are Instagram-worthy.

Some of the village houses are made of mud—though most have now been replaced by cement and tiles. These mud houses, over time, will simply return to the earth (see pic below).

There is another family in the village that makes brooms out of palm leaves and sells them locally. The two brothers - Anuj and Akash are incredibly creative, have a brilliant sense of humour and can also weave the leaves into beautiful objects like bouquets and roses.

What’s even more interesting about these artisans is that some of them have designated homes they sell their products to. Another artisan making the same thing cannot sell to those houses. The idea is that artisans don’t compete for each other’s market share—even in a village economy as small as this.

In contrast, during my MBA program, we spent a lot of time learning how to grow our market share in extremely competitive markets. Most people running businesses in the city are occupied with this question. And yet, here was a simple example of how smaller communities can prioritize harmony over competition.

There is a quiet intelligence in the way village life is designed—where nothing is wasted, and no one is left out.

That’s all for today! Thanks for reading this edition of Break the Bubble. See you next week.

Opportunity of the week

The below post has been taken from ICC’s LinkedIn page.

The India Climate Collaborative (ICC) established in 2020 is looking for a Program Manager – Heat to lead the implementation of their emerging strategy on extreme heat resilience and climate-friendly cooling.

This is a critical mid-level role focused on converting ideas into action, driving program execution, building a domestic donor coalition, and strengthening cross-sector partnerships.

More details about the role and responsibilities here.

Recommendations of the week

I invite you to visit some of India’s villages:

The one I went to is Indrana, one hour from Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh

Paradsinga, again in MP, where a community knows how to make paper out of grass.

Belagaon, near Nagpur in Maharashtra, where an industrial designer has a Maker studio where you can learn welding, carpentry and more.

Mendha Lekha, one of India’s most famous villages, again in Maharashtra where you can still find systems of self governance and commons looked after by the villagers.

Bonus: If the above aren’t enough to satiate your thirst, here’s a list of India’s cleanest villages that you must visit and explore. Let me know how it goes :)

Thanks so much Ira for writing with profound yet simple insights from the experience.